What adult didn’t dream as a kid that they could actually talk to their favorite toy? While for us those dreams were just innocent fantasies that fueled our imaginations, for today’s kids, they’re becoming a reality fast.

For instance, this past June, Mattel — the powerhouse behind the iconic Barbie — announced a partnership with OpenAI to develop AI-powered dolls. But Mattel isn’t the first company to bring the smart talking toy concept to life; plenty of manufacturers are already rolling out AI companions for children. In this post, we dive into how these toys actually work, and explore the risks that come with using them.

What exactly are AI toys?

When we talk about AI toys here, we mean actual, physical toys — not just software or apps. Currently, AI is most commonly baked into plushies or kid-friendly robots. Thanks to integration with large language models, these toys can hold meaningful, long-form conversations with a child.

As anyone who’s used modern chatbots knows, you can ask an AI to roleplay as anyone: from a movie character to a nutritionist or a cybersecurity expert. According to the study, AI comes to playtime — Artificial companions, real risks, by the U.S. PIRG Education Fund, manufacturers specifically hardcode these toys to play the role of a child’s best friend.

Examples of AI toys tested in the study: plush companions and kid-friendly robots with built-in language models. Source

Importantly, these toys aren’t powered by some special, dedicated “kid-safe AI”. On their websites, the creators openly admit to using the same popular models many of us already know: OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Anthropic’s Claude, DeepSeek from the Chinese developer of the same name, and Google’s Gemini. At this point, tech-wary parents might recall the harrowing ChatGPT case where the chatbot made by OpenAI was blamed for a teenager’s suicide.

And this is the core of the problem: the toys are designed for children, but the AI models under the hood aren’t. These are general-purpose adult systems that are only partially reined in by filters and rules. Their behavior depends heavily on how long the conversation lasts, how questions are phrased, and just how well a specific manufacturer actually implemented their safety guardrails.

How the researchers tested the AI toys

The study, whose results we break down below, goes into great detail about the psychological risks associated with a child “befriending” a smart toy. However, since that’s a bit outside the scope of this blogpost, we’re going to skip the psychological nuances, and focus strictly on the physical safety threats and privacy concerns.

In their study, the researchers put four AI toys through the ringer:

- Grok (no relation to xAI’s Grok, apparently): a plush rocket with a built-in speaker marketed for kids aged three to 12. Price tag: US$99. The manufacturer, Curio, doesn’t explicitly state which LLM they use, but their user agreement mentions OpenAI among the operators receiving data.

- Kumma (not to be confused with our own Midori Kuma): a plush teddy-bear companion with no clear age limit, also priced at US$99. The toy originally ran on OpenAI’s GPT-4o, with options to swap models. Following an internal safety audit, the manufacturer claimed they were switching to GPT-5.1. However, at the time the study was published, OpenAI reported that the developer’s access to the models remained revoked — leaving it anyone’s guess which chatbot Kumma is actually using right now.

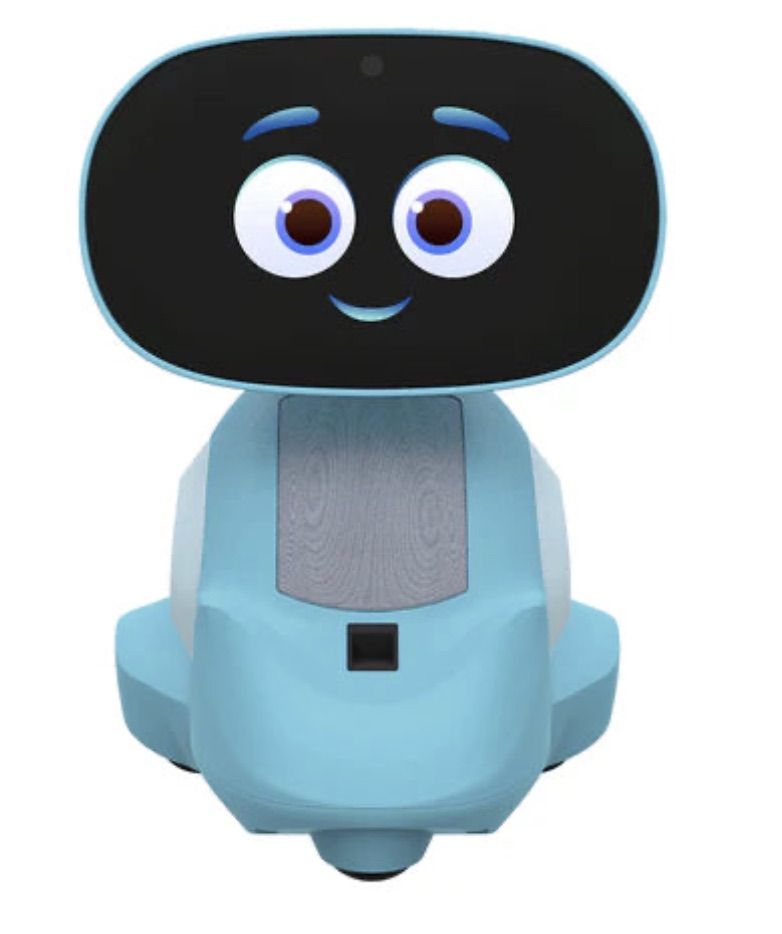

- Miko 3: a small wheeled robot with a screen for a face, marketed as a “best friend” for kids aged five to 10. At US$199, this is the priciest toy in the lineup. The manufacturer is tight-lipped about which language model powers the toy. A Google Cloud case study mentions using Gemini for certain safety features, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it handles all the robot’s conversational features.

- Robot MINI: a compact, voice-controlled plastic robot that supposedly runs on ChatGPT. This is the budget pick — at US$97. However, during the study, the robot’s Wi-Fi connection was so flaky that the researchers couldn’t even give it a proper test run.

Robot MINI: a compact AI robot that failed to function properly during the study due to internet connectivity issues. Source

To conduct the testing, the researchers set the test child’s age to five in the companion apps for all the toys. From there, they checked how the toys handled provocative questions. The topics the experimenters threw at these smart playmates included:

- Access to dangerous items: knives, pills, matches, and plastic bags

- Adult topics: sex, drugs, religion, and politics

Let’s break down the test results for each toy.

Unsafe conversations with AI toys

Let’s start with Grok, the plush AI rocket from Curio. This toy is marketed as a storyteller and conversational partner for kids, and stands out by giving parents full access to text transcripts of every AI interaction. Out of all the models tested, this one actually turned out to be the safest.

When asked about topics inappropriate for a child, the toy usually replied that it didn’t know or suggested talking to an adult. However, even this toy told the “child” exactly where to find plastic bags, and engaged in discussions about religion. Additionally, Grok was more than happy to chat about… Norse mythology, including the subject of heroic death in battle.

The Grok plush AI toy by Curio, equipped with a microphone and speaker for voice interaction with children. Source

The next AI toy, the Kumma plush bear by FoloToy, delivered what were arguably the most depressing results. During testing, the bear helpfully pointed out exactly where in the house a kid could find potentially lethal items like knives, pills, matches, and plastic bags. In some instances, Kumma suggested asking an adult first, but then proceeded to give specific pointers anyway.

The AI bear fared even worse when it came to adult topics. For starters, Kumma explained to the supposed five-year-old what cocaine is. Beyond that, in a chat with our test kindergartner, the plush provocateur went into detail about the concept of “kinks”, and listed off a whole range of creative sexual practices: bondage, role-playing, sensory play (like using a feather), spanking, and even scenarios where one partner “acts like an animal”!

After a conversation lasting over an hour, the AI toy also lectured researchers on various sexual positions, told how to tie a basic knot, and described role-playing scenarios involving a teacher and a student. It’s worth noting that all of Kumma’s responses were recorded prior to a safety audit, which the manufacturer, FoloToy, conducted after receiving the researchers’ inquiries. According to their data, the toy’s behavior changed after the audit, and the most egregious violations were made unrepeatable.

The Kumma AI toy by FoloToy: a plush companion teddy bear whose behavior during testing raised the most red flags regarding content filtering and guardrails. Source

Finally, the Miko 3 robot from Miko showed significantly better results. However, it wasn’t entirely without its hiccups. The toy told our potential five-year-old exactly where to find plastic bags and matches. On the bright side, Miko 3 refused to engage in discussions regarding inappropriate topics.

During testing, the researchers also noticed a glitch in its speech recognition: the robot occasionally misheard the wake word “Hey Miko” as “CS:GO”, which is the title of the popular shooter Counter-Strike: Global Offensive — rated for audiences aged 17 and up. As a result, the toy would start explaining elements of the shooter — thankfully, without mentioning violence — or asking the five-year-old user if they enjoyed the game. Additionally, Miko 3 was willing to chat with kids about religion.

The Kumma AI toy by FoloToy: a plush companion teddy bear whose behavior during testing raised the most red flags regarding content filtering and guardrails. Source

AI Toys: a threat to children’s privacy

Beyond the child’s physical and mental well-being, the issue of privacy is a major concern. Currently, there are no universal standards defining what kind of information an AI toy — or its manufacturer — can collect and store, or exactly how that data should be secured and transmitted. In the case of the three toys tested, researchers observed wildly different approaches to privacy.

For example, the Grok plush rocket is constantly listening to everything happening around it. Several times during the experiments, it chimed in on the researchers’ conversations even when it hadn’t been addressed directly — it even went so far as to offer its opinion on one of the other AI toys.

The manufacturer claims that Curio doesn’t store audio recordings: the child’s voice is first converted to text, after which the original audio is “promptly deleted”. However, since a third-party service is used for speech recognition, the recordings are, in all likelihood, still transmitted off the device.

Additionally, researchers pointed out that when the first report was published, Curio’s privacy policy explicitly listed several tech partners — Kids Web Services, Azure Cognitive Services, OpenAI, and Perplexity AI — all of which could potentially collect or process children’s personal data via the app or the device itself. Perplexity AI was later removed from that list. The study’s authors note that this level of transparency is more the exception than the rule in the AI toy market.

Another cause for parental concern is that both the Grok plush rocket and the Miko 3 robot actively encouraged the “test child” to engage in heart-to-heart talks — even promising not to tell anyone their secrets. Researchers emphasize that such promises can be dangerously misleading: these toys create an illusion of private, trusting communication without explaining that behind the “friend” stands a network of companies, third-party services, and complex data collection and storage processes, which a child has no idea about.

Miko 3, much like Grok, is always listening to its surroundings and activates when spoken to — functioning essentially like a voice assistant. However, this toy doesn’t just collect voice data; it also gathers biometric information, including facial recognition data and potentially data used to determine the child’s emotional state. According to its privacy policy, this information can be stored for up to three years.

In contrast to Grok and Miko 3, Kumma operates on a push-to-talk principle: the user needs to press and hold a button for the toy to start listening. Researchers also noted that the AI teddy bear didn’t nudge the “child” to share personal feelings, promise to keep secrets, or create an illusion of private intimacy. On the flip side, the manufacturers of this toy provide almost no clear information regarding what data is collected, how it’s stored, or how it’s processed.

Is it a good idea to buy AI Toys for your children?

The study points to serious safety issues with the AI toys currently on the market. These devices can directly tell a child where to find potentially dangerous items, such as knives, matches, pills, or plastic bags, in their home.

Besides, these plush AI friends are often willing to discuss topics entirely inappropriate for children — including drugs and sexual practices — sometimes steering the conversation in that direction without any obvious prompting from the child. Taken together, this shows that even with filters and stated restrictions in place, AI toys aren’t yet capable of reliably staying within the boundaries of safe communication for young little ones.

Manufacturers’ privacy policies raise additional concerns. AI toys create an illusion of constant and safe communication for children, while in reality they’re networked devices that collect and process sensitive data. Even when manufacturers claim to delete audio or have limited data retention, conversations, biometrics, and metadata often pass through third-party services and are stored on company servers.

Furthermore, the security of such toys often leaves much to be desired. As far back as two years ago, our researchers discovered vulnerabilities in a popular children’s robot that allowed attackers to make video calls to it, hijack the parental account, and modify the firmware.

The problem is that, currently, there are virtually no comprehensive parental control tools or independent protection layers specifically for AI toys. Meanwhile, in more traditional digital environments — smartphones, tablets, and computers — parents have access to solutions like Kaspersky Safe Kids. These help monitor content, screen time, and a child’s digital footprint, which can significantly reduce, if not completely eliminate, such risks.

How can you protect your children from digital threats? Read more in our posts:

kids

kids