Android constantly tightens app restrictions to prevent scammers from using malicious software to steal money, passwords, and users’ private secrets. However, a new vulnerability dubbed Pixnapping all of Android’s protective layers, and allows an attacker to imperceptibly read image pixels from the screen — essentially taking a screenshot. A malicious app with zero permissions can see passwords, bank account balances, one-time codes, and anything else the owner views on the screen. Fortunately, Pixnapping is currently a purely research-based project and is not yet being actively exploited by threat actors. The hope is that Google will thoroughly patch the vulnerability before the attack code is integrated into real-world malware. As of now, the Pixnapping vulnerability (CVE-2025-48561) likely affects all modern Android smartphones — including those running the latest Android versions.

Why screenshots, media projection, and screen reading are dangerous

As demonstrated by the SparkCat OCR stealer we discovered, threat actors have already mastered image processing. If an image on a smartphone contains a valuable piece of information, the malware can detect it, perform optical character recognition directly on the phone, and then exfiltrate the extracted data to the attacker’s server. SparkCat is particularly noteworthy because it managed to infiltrate official app marketplaces, including the App Store. It would not be difficult for a malicious Pixnapping-enabled app to replicate this trick — especially given that the attack requires zero special permissions. An app that appears to offer a legitimate, useful feature could simultaneously and silently send one-time multi-factor authentication codes, cryptowallet passwords, and any other information to scammers.

Another popular tactic used by malicious actors is to view the required data as it’s shown, in real-time. For this social engineering approach, the victim is contacted via a messaging app and, under various pretexts, convinced to enable screen sharing.

Anatomy of the Pixnapping attack

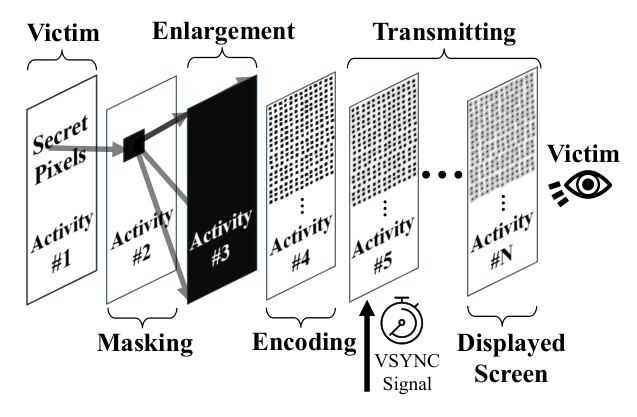

The researchers were able to screenshot content from other apps by combining previously known methods of stealing pixels from browsers and from ARM phone graphics processing units (GPUs). The attacking app silently overlays translucent windows atop the target information and then measures how the video system combines the pixels of these layered windows into a final image.

As far back as 2013, researchers described an attack that allowed one website to load another within part of its own window (via an iframe) and, by performing legitimate operations of image layering and transformation, infer exactly what was drawn or written on the other site. While modern browsers have mitigated that specific attack, a group of U.S. researchers have now figured out how to apply the same core principle to Android.

The malicious app first sends a system call to the target app. In Android, this is known as an Intent. Intents typically enable not only simple app launching but also things like immediately opening a browser for a specific URL or a messaging app for a specific contact’s chat. The attacking app sends an Intent designed to force the target app to render the screen with the sensitive information. Special hidden launch flags are used. The attacking app then sends a launch Intent to itself. This specific combination of actions allows the victim app to not appear on the screen at all, yet it still renders the information sought by the attacker in its window in the background.

In the second stage of the attack, the malicious app overlays the hidden window of the victim app with a series of translucent windows, each of which covers and blurs the content beneath it. This complex arrangement remains invisible to the user, but Android dutifully calculates how this combination of windows should look if the user were to bring it to the foreground.

The attacking app can only directly read the pixels from its own translucent windows; the final combined image, which incorporates the victim app’s screen content, is not directly accessible to the attacker. To bypass this restriction, the researchers employ two ingenious tricks: (i) the specific pixel to be stolen is isolated from its surroundings by overlaying the victim app with a mostly opaque window that has a single transparent point precisely over the target pixel; (ii) a magnifying layer is then placed on top of this combination, consisting of a window with heavy blurring enabled.

To decipher the resulting mush and determine the value of the pixel at the very bottom, the researchers leveraged another known vulnerability, GPU.zip (this may look like a file link, but it actually leads to the site with showing a research paper). This vulnerability is based on the fact that all modern smartphones compress the data of any images being sent from the CPU to the GPU. This compression is lossless (like a ZIP file), but the speed of packing and unpacking changes depending on the information being transmitted. GPU.zip permits an attacker to measure the time it takes to compress the information. By timing these operations, the attacker can infer what data is being transferred. With the help of GPU.zip, the isolated, blurred, and magnified single pixel from the victim app’s window can be successfully read by the attacking app.

Stealing something meaningful requires repeating the entire pixel-stealing process hundreds of times, as it needs to be applied to each point separately. However, this is entirely feasible within a short time frame. In a video demonstration of the attack, a six-digit code from Google Authenticator was successfully extracted in just 22 seconds while it was still valid.

How Android protects screen confidentiality

Google engineers have nearly two decades of experience combating various privacy attacks, which has resulted in a layered defense built against illegal capture of screenshots and videos. A complete list of these measures would span several pages, so we only list some key protections:

- The FLAG_SECURE window flag prevents the operating system from taking screenshots of content.

- Access to media projection tools (capturing screen content as a media stream) requires explicit user confirmation, and can only be performed by an app that’s visible and active.

- Tight restrictions are placed on access to administrative services like AccessibilityService and the ability to render app elements over other apps.

- One-time passwords and other secret data are hidden automatically if media projection is detected.

- Android restricts apps from accessing other apps’ data. Additionally, apps cannot request a full list of all installed apps on the smartphone.

Unfortunately, Pixnapping bypasses all these existing restrictions and requires absolutely no special permissions. The attacking app only needs two fundamental capabilities: to render its own windows and to send system calls (Intents) to other apps. These are basic building blocks of Android functionality, so they’re very difficult to restrict.

Which devices are affected by Pixnapping, and how to defend oneself

The attack’s viability was confirmed on Android versions 13–16 across Google Pixel devices from generations 6–9, as well as Samsung Galaxy S25. The researchers believe the attack will be functional on other Android devices as well, as all the mechanisms used are standard. However, there may be nuances related to the implementation of the second phase of the attack (the pixel magnification technique).

Google released a patch in September after being notified of the attack in February. Unfortunately, the chosen method for fixing the vulnerability proved to be insufficiently reliable, and the researchers quickly devised a way to bypass the patch. A new attempt to eliminate the vulnerability is planned for Google’s December update release. As for GPU.zip, there are no plans to issue a patch for this specific data leakage channel. At least, no smartphone GPU manufacturer has announced plans to that effect since the flaw became public knowledge in 2024.

User options to defend against Pixnapping are limited. We recommend the following measures:

- Promptly update to the latest version of Android with all current security patches.

- Avoid installing apps from unofficial sources, and exercise caution with apps from official stores if they’re very new, have low download counts, or are poorly rated.

- Ensure that a full-fledged security system is used on your phone, such as Kaspersky for Android.

What other non-standard Android attack methods exist:

Android

Android